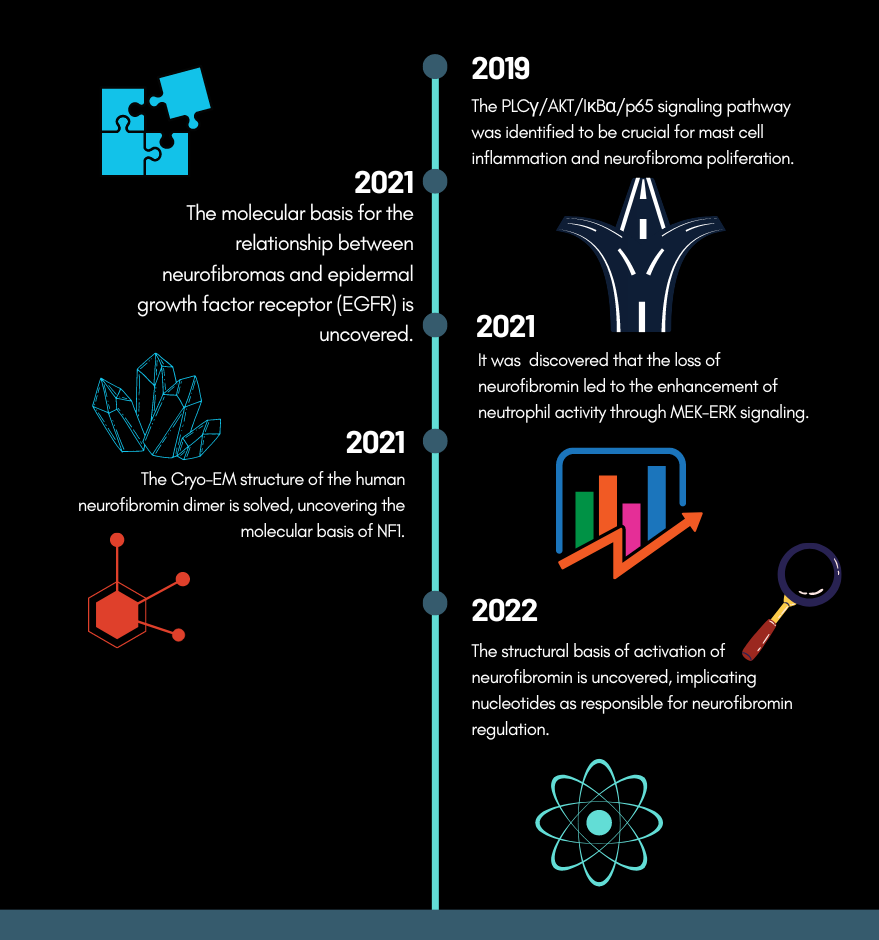

Capstone Project: Neurofibromatosis Type I

Science and medicine have progressed beyond belief in the modern era. In the past 2 decades, we have discovered every human gene, found ways to 3D print human body parts, developed a vaccine in record time, and much more. No matter the advancements we make, however, disease always rears its ugly head – it seems to be an unavoidable consequence of the human condition. With countless diseases afflicting humans, what makes neurofibromatosis type I (NF1) worth reading about? By learning about NF1, it is impossible not to be amazed by the complexity within ourselves, and this disease exploits that quality.

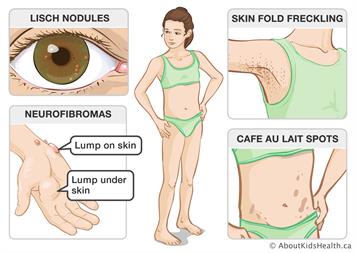

NF1 affects 1 in 3,000 people and is traceable back to 13th and 16th-century writings.1,2 NF1 leads to a multitude of symptoms including light brown spots (Cafe au lit macules), freckles of the armpit and groin (axillary and inguinal freckles, respectively), and most notably, plexiform and dermal neurofibromas.3 Neurofibromas are noncancerous tumors that grow along nerves in the body. They appear as small “bumps,” roughly 2 mm in diameter, but may grow up to 20 mm and become malignant (cancerous) over time.3 Common, non-visible symptoms include learning disabilities and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.3 NF1 is usually diagnosed by a physical exam, however, many of the features of NF1 are not apparent until the age of 5.4 The age-dependent and variable nature of disease diagnosis is a major limitation in the current testing for NF1. Variability is a word intrinsic to NF1, at every level – genetic, molecular, cellular, and bodily – uniformity is without a trace.

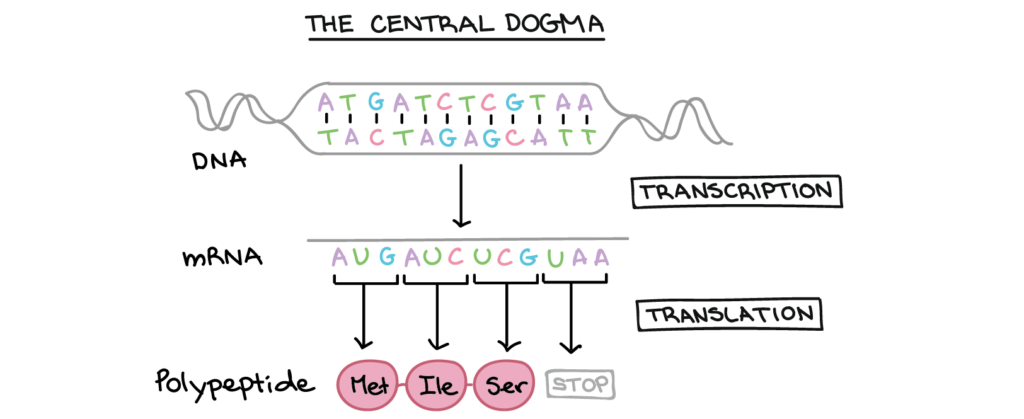

The human body works like computer code. Inputting strings of code into a computer will tell it to perform certain functions, culminating in a usable product. Similarly, our genetic code contains genes that code for specific products, called proteins, that perform a myriad of functions. Rather than binary digits, our genetic code uses four “letters” (molecules) to code for proteins. Genes can have these letters unintentionally changed, which is known as being mutated. Mutations can disrupt the function of proteins and lead to disease.

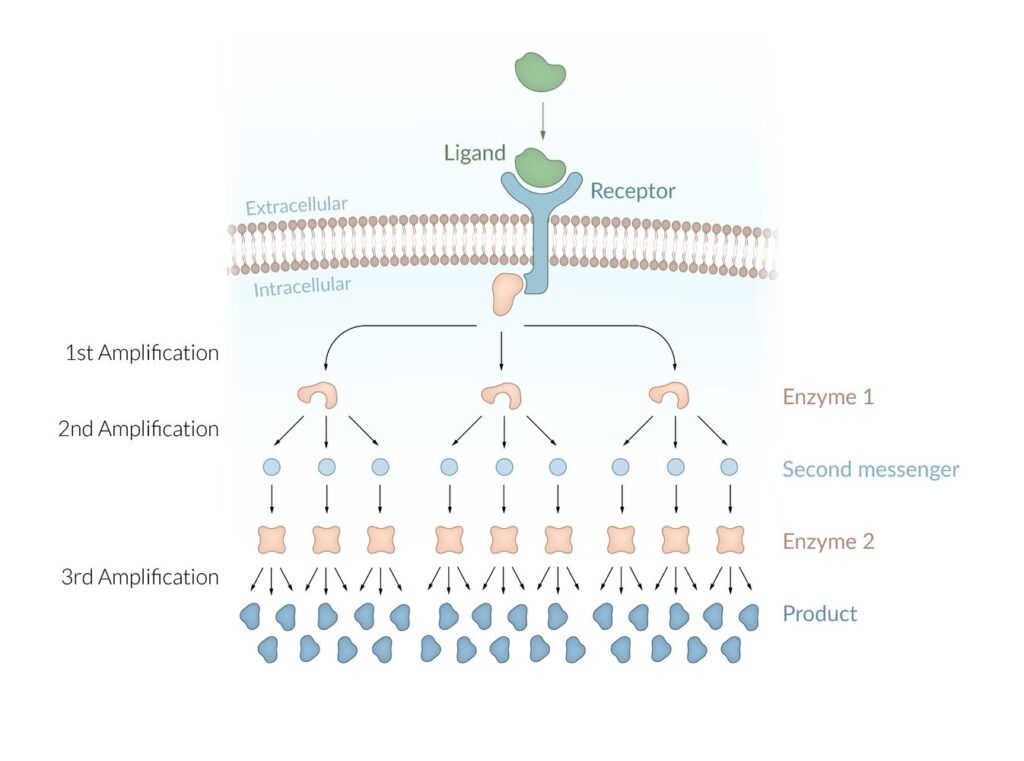

In 1990, the first gene mutation to cause NF1 was discovered on chromosome number 17.7,8 Further studies on the protein this gene produced, neurofibromin, found significant similarity to a previously studied protein in yeast, named IRA1, which is similar to a protein in humans, the mammalian GTPase-activation protein (GAP).7 GAPs are crucial for regulating cells. They control pathways that regulate cell growth, signaling, and other processes. Therefore, mutations in regulatory proteins can have profound and compounding effects.

As a GAP, neurofibromin is responsible for turning off pathways that allow cells to proliferate, which may sound bad, but remember, the brake is the most important part of the bike. When neurofibromin is inhibited, the pathways for cellular growth cannot be stopped, leading to uncontrolled cell growth, in other words, tumors.

Proteins, like legos, are built out of individual blocks called amino acids. Mutations at the genetic level lead to the wrong “blocks” being used to build the protein, disrupting its final structure. The molecular structure of neurofibromin was found in 2021, providing insight into the protein structural causes for NF1.11 Neurofibromin has been identified to be a very fragile protein, and it requires pairing with itself in order to operate normally.11 Mutations impacting its ability to self-pair have been associated with NF1.11

The reason NF1 causes tumors to grow along the nervous system is due to the types of cells that NF1 afflicts. One of these cell types is called Schwann cells.11 Schwann cells themselves are not neurons (signaling cells in the nervous system), rather, they are cells that assist neurons by providing them with nutrients, replacing damaged neurons, and helping neurons send messages quicker. When neurofibromin is inhibited in Schwann cells because of NF1, they are no longer able to provide support to the nervous system. This may lead to deterioration of nervous system function and the inability to control neuronal cell growth. Furthermore, NF1 affects key immune cells, macrophages, as well as mast cells, which were shown to be crucial for setting the environment of NF1 tumors.12

Much is still unknown about neurofibromatosis, largely because of how variable the disease is at every level that it acts on. Although daunting, this veil should inspire wonder in researchers and readers like yourself! There is much to uncover about the disease, which means there is much more to uncover about ourselves! If you wish to learn a little bit more about this disease, and about yourself, please skim through my website!

If the business of physics is ever finished, the world will be a much less interesting place in which to live, which is why I am happy to leave you with loose ends, tantalizing hints, and the prospect of more stories to be told…

John Gribbin, In Search of Schrödinger’s Cat

7 Comments

Max Dundon · May 2, 2022 at 3:42 pm

Do you think that because so much is unknown about neurofibromatosis, we will find positive out comes of research or are negative outcomes more likely? Do you predict more research and findings to come very soon or will it take longer than would be appreciated?

admin · May 12, 2022 at 2:37 pm

Thanks for the comment, Max! This is an interesting thought to ponder. So far, research into NF1 has continued to add to the complexity of the disease, with little insight into treatment options (other than the drug Selumetinib that was approved for use in children with NF1). Genetically, the cause for disease is variable and marked by various, arguably unquantifiable mutations. However, it is known that these genetic mutations lead to the NF1 gene product, the protein neurofibromin, from performing its normal roles in the cell. Although the genetic mutations are difficult to understand, the cause of disease at the protein level is known. More studies on the fragility of the affected protein may hopefully provide insight into molecules that can be made and used to counter the effects of the genetic mutations, or supplement affected cells with a replacement for neurofibromin.

In terms of how soon findings will come out, this question might best be answered from a non-scientific perspective. Research requires funding, and funding is hard to come by. The funding of research projects is dependent on many factors, with a major one being the research’s relevance to pertinent scientific topics of the time. For example, a couple of decades ago, research on the gut microbiome (the “good” bacteria that live in our gut) may not have been funded, since cancer took the research forefront towards the end of the 20th century. However, microbiome is the thing to study today. Similarly, as I stated in my historical section, research into NF1 was really kickstarted by the social allure that people had towards Joseph Merrick. Since the Selumetinib drug study came out in 2016, pharmaceutical companies may see value in pursuing NF1 as an avenue for increased profits, increasing research into this area.

Denis · May 2, 2022 at 3:52 pm

Hey Michael! Nice article. I was wondering, do you believe it to be necessary for people to be getting screened for NF1 on a consistent basis?

admin · May 12, 2022 at 2:43 pm

Hey, Denis! Thank you for such a great question! The easy answer to this question is based on inheritance. If a family has a history of NF1, people in that lineage should definitely be screened for the disease (especially since the mutation is dominant. Which means that you only need one copy of the mutation to exhibit the disease). Otherwise, it is difficult to say. As noted in the clinical manifestations page, upwards of 90% of NF1 cases are diagnosed by the age of 8, it is a disease that impacts people very early in their lives. Furthermore, there is no agreed upon genetic test for NF1, since the mutations at the gene level that cause NF1 are almost impossible to predict. However, we do know that the milieu of gene mutations causing NF1 all impact the neurofibromin protein. Hypothetically, a technique can be designed to take patient cells, isolate neurofibromin, and test whether or not its functioning. Although this sounds like an ideal solution, it is not practical due to the time and money this would require, as well as the fragility of the neurofibromin protein itself – it may not operate as expected anyway, once it’s out of the cell! However, it is important to note that screening for the disease prior to its onset will likely not change the outcome, since there are no known preventative measures for the disease. If a consensus does emerge on how to genetically test for the disease, then prenatal screening (testing a baby during pregnancy) can definitely be an option!

Jonathan · May 2, 2022 at 5:31 pm

Great read! I loved your use of analogies to legos, bikes, and computers to clarify difficult topics, and the use of clearly labeled images which provided greater visual clarity to the topics discussed.

admin · May 11, 2022 at 4:15 pm

Thanks, Johnny!

Felicia · May 3, 2022 at 12:04 am

Great post! Something that stood out to me is the variable nature of neurofibromatosis type I, and this made me wonder if there are other major symptoms of NF1 that are not currently known to be associated with NF1. Additionally, what causes NF1 to affect certain types of cells over other kinds of cells?