Disease Discovery & Clinical Manifestations

Disease Discovery:

The rise of neurofibromatosis type I (NF1) to academic relevancy was born out of discrimination, outcasting, and shame. As written by Siddhartha Mukherjee in The Emperor of All Maladies, “To name an illness is to describe a certain condition of suffering – a literary act before it becomes a medical one. A patient, long before he becomes the subject of medical scrutiny, is, at first, simply a storyteller, a narrator of suffering – a traveler who has visited the kingdom of the ill. To relieve an illness, one must begin, then, by unburdening its story.” And this story begins with a man named Joseph Merrick, who, sadly, is more widely known as the “Elephant Man.”

Merrick was born in 1862, and was phenotypically unremarkable at birth. Quickly, by the age of 5, Merrick had begun to develop bony and fleshy tumors around his body, significantly restricting his life.1 In 1884, Merrick began to be exhibited as “The Elephant Man” in a human oddities show around Europe.1 Merrick was the spotlight of social entertainment and scientific curiosity. He later would state that the experience made him feel like “an animal in a cattle market.”1 In 1909, the dermatologist Parkes incorrectly claimed that Joseph Merrick suffered from NF1.2 The cultural spotlight led to increased research into NF1 during the 20th century. However, in 1986 it became clear that Joseph Merrick actually had Proteus syndrome, not NF1.2 The perpetuation of the false connection between NF1 and the “Elephant Man” increases the burden of those with NF1. In summary, the propulsion of NF1 into academic relevance is a consequence of exploitation and humiliation. The severity of clinical onset sadly makes the social consequences of having this disease inextricable with its clinical consequences. Throughout this study into NF1, it is important to acknowledge these roots, and be reminded of the emotional and social burden that accompanies the onset of disease.

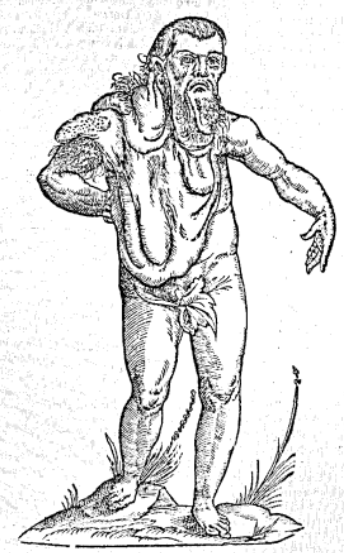

Although the disease became well known in the 20th century, depictions of the disease have been identified in artwork as early as the 13th and 16th centuries.

In figure 1, multiple “goiters” hanging down from the neck can be seen, as well as a deformity of the foot. Furthermore, the inclusion of amphibia with many scales and bumps in this illustration may be reflective of the author’s attempt to describe the person being drawn. The scales on the creatures drawn may be analogous to the way the depicted person looks, potentially indicating the existence of several plexiform neurofibromas.3 The described patient in figure 2 was stated to be Indian, which may be true, but also, this attribution of place must be analyzed through the cultural context in which this description was made. The Renaissance European conception of monsters is based on that of the Greeks, which were races thought to have lived far East, mostly in India.4 Therefore, it is worth noting that this early description may be pervaded with racism and discrimination, misconstruing the true geographic origin of this patient.

Already we see how depictions of patients with NF1 are pervaded with exclusionary sentiment, connected to lowly creatures, and considered as negative anomalies.

The discovery of NF1 is attributed to the German Pathologist Friederich Daniel Von Recklinghausen. In 1882, the German pathologist wrote about two cases of neurofibromatosis, describing the canonical appearance of the disease, and postulating that these tumors grew from connective tissue.8 Because of this association, NF1 is also known as Von Recklinghausen’s disease.

Clinical Manifestations

As will be discussed, NF1 is a disease with extreme variability at the genotype and phenotype levels, and correlations between the variabilities have not been elucidated as of yet. The symptoms of NF1 are quite extreme and visible. Early descriptions of NF1 provide insight into the difficulty of objectively classifying aspects of the disease. In a 1908 case description by authors Morris & Fox, they stated that “[countless] tumors were distributed all over the body,” and categorized the tumors into two types: “soft, almost fluctuating, subcutaneous masses,” and tumors that were firm, “projecting from the surface of the skin.”5 This latter type was also noted to be “gelatinous” to the touch. The “type” of tumor differed based on their location on the body.

The phenotypic variability of disease is correlated with severity of disease (as increased onset of symptoms will lead to more severe disease). The most common dermatologic symptoms are discussed below:

Other common, non-dermatologic clinical manifestations of the disease include learning disabilities in children and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.6

Diagnosis of NF1 is usually conducted by a physical exam. However, many of the listed features of NF1 are not apparent until the age of five (97% of NF1 patients are diagnosed by eight years old).7 The age-dependent nature of disease diagnosis is a major limitation in the current way of testing for NF1. Techniques such as genetic testing have not been implemented as a means of diagnosis due to the wide range of mutations capable of causing NF1. As will be discussed, NF1 is a disease whose effects are exerted via biochemical mechanisms. Therefore, improving the biochemical characterization of the disease will allow for better diagnosis, treatment, and understanding of the disease.

The prognosis of NF1 is quite positive. If there are no outstanding complications, life expectancy of people with NF1 is normal, however, the risk of developing malignant tumors may shorten life span.

There are no treatments for NF1. Tumors that cause patients to experience pain/lose function can be removed. In 2016, Dombi et al. conducted a study on the ability of the selective inhibitor of MEK 1 and 2, selumetinib, to treat NF1.7 In mouse models, they found a consistent reduction in tumor volume and a slowing of tumor growth.7 When tested on children with severe tumors, these positive results were reproduced.7 Currently, selumetinib has been approved to be used in children with severe tumors, as it reduces tumor volume.7

Works Cited

(7) Dombi, E.; Baldwin, A.; Marcus, L. J.; Fisher, M. J.; Weiss, B.; Kim, A.; Whitcomb, P.; Martin, S.; Aschbacher-Smith, L. E.; Rizvi, T. A.; Wu, J.; Ershler, R.; Wolters, P.; Therrien, J.; Glod, J.; Belasco, J. B.; Schorry, E.; Brofferio, A.; Starosta, A. J.; Gillespie, A.; Doyle, A. L.; Ratner, N.; Widemann, B. C. Activity of Selumetinib in Neurofibromatosis Type 1–Related Plexiform Neurofibromas. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375 (26), 2550–2560. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1605943.

For a complete list of sources used, please access the Annotated Bibliography.

5 Comments

John Santa Maria · May 1, 2022 at 8:07 pm

Thanks for a great overview of NF1 history, cause, current treatments, and etiology.

You mentioned selumetinib is an approved therapy for NF1 by targeting MEK signaling. Are there other pathways that have been investigated to treat this disease? For example, you mentioned involvement of the JAK/STAT and EGFR axes, do approved JAK/EGFR inhibitors (e.g. tofacitinib, erlotinib, etc.) have any efficacy in treating the disease?

You also mentioned that many mutations have been found in NF1. Is it known what factors contribute to the hypermutability of this genetic locus? Due to its dominant genetic inheritance, is NF1 a candidate for gene therapy, and are there diagnostics to warn parents when they may be at risk of passing on a disease allele?

Finally, you mentioned involvement of immune cells in promoting rather than attenuating plexiform neurofibromas. Does aberrant NF1 signaling regulate downstream immune evasion effectors?

Great work and thanks again for the educational blog post 🙂

admin · May 12, 2022 at 4:38 pm

Thank you so much for this comment, John! Research on the treatment of tumors through inhibiting other pathways has been done, though not all of it is relevant to NF1. Although most of the tumors in NF1 are benign neurofibromas, these may turn into malignant peripheral nerve sheet tumors (MPNSTs) which are deadly and are known to be highly resistant. Grit et al. studied the effect of a MET inhibitor (capmatinib), a MEK inhibitor (trametinib), and doxorubicin on MPNSTs.1 MET and MEK inhibition caused tumors to stop growing for a period, before reinitiating growth.1 Treatment with doxorubicin caused the tumor to adopt kinome adaptations, allowing it to grow.1 Qureshy et al. published a study in 2021 where they targeted the JAK/STAT pathway in solid tumors and found that JAK inhibitors decreased STAT activation, cell proliferation, cell survival, and made cells more sensitive to current cancer therapies.2 This study did not test any NF1-associated tumors. Interestingly enough, there is one case report that describes a patient with NF1 taking the JAK-inhibitor, tofacitinib. In this report, treatment with the JAK inhibitor led to an “eruption” of neurofibromas, which regressed only after tofacitinib therapy was stopped.3

There are upwards of thousands of associated gene mutations leading to NF1. Upon analysis of the NF1 gene in 67 NF1 patients, mutations were found to be evenly distributed along the gene’s coding sequence, with exons 10a-10c and E37 being more mutation-rich.4 Although there is no definitive reason for the NF1 gene being so prone to mutations, the authors in this study consider somatic mosaicism as a potential explanation.4

There are currently no viable gene therapies for NF1. Since it is a dominant gene, parents would know if they are at risk of passing on a disease allele if they or their partner exhibits NF1. In terms of being able to predict whether a spontaneous mutation will occur in their child, leading to NF1, none of the available literature implies that this is possible.

I love this question! The involvement of immune cells in promoting NF1 is very interesting, it instilled a sense of betrayal in me once I learned about it. Macrophages, surprisingly, make up more than half of the cells contained in neurofibromas. Macrophages are actually initially restrictive against developing neurofibromas.5 However, once neurofibromas are established, the macrophages assist the tumor in creating blood vessels, they release cytokines and proteases that enhance tumor cell proliferation, and they promote angiogenesis.5

Grit JL, Pridgeon MG, Essenburg CJ, Wolfrum E, Madaj ZB, Turner L, Wulfkuhle J, Petricoin EF 3rd, Graveel CR, Steensma MR. Kinome Profiling of NF1-Related MPNSTs in Response to Kinase Inhibition and Doxorubicin Reveals Therapeutic Vulnerabilities. Genes (Basel). 2020 Mar 20;11(3):331. doi: 10.3390/genes11030331. PMID: 32245042; PMCID: PMC7141129.

Qureshy Z, Johnson DE, Grandis JR. Targeting the JAK/STAT pathway in solid tumors. J Cancer Metastasis Treat. 2020;6:27. Epub 2020 Aug 21. PMID: 33521321; PMCID: PMC7845926.

Adam Rischin, Thilinie De Silva, Kim Le Marshall, Reversible eruption of neurofibromatosis associated with tofacitinib therapy for rheumatoid arthritis, Rheumatology, Volume 58, Issue 6, June 2019, Pages 1111–1113, https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kez012

Messiaen LM, Callens T, Mortier G, Beysen D, Vandenbroucke I, Van Roy N, Speleman F, Paepe AD. Exhaustive mutation analysis of the NF1 gene allows identification of 95% of mutations and reveals a high frequency of unusual splicing defects. Hum Mutat. 2000;15(6):541-55. doi: 10.1002/1098-1004(200006)15:6<541::AID-HUMU6>3.0.CO;2-N. PMID: 10862084.

Prada, C.E., Jousma, E., Rizvi, T.A. et al. Neurofibroma-associated macrophages play roles in tumor growth and response to pharmacological inhibition. Acta Neuropathol 125, 159–168 (2013). https://doi-org.muhlenberg.idm.oclc.org/10.1007/s00401-012-1056-7

Jonathan · May 2, 2022 at 6:01 pm

If it’s been so long since the discovery that Joseph Merrick actually suffered from Proteus syndrome, rather than NF1, why does the myth that he suffered from NF1 persist? Have there been many large-scale efforts made to clarify this misconception and educate the public? What might this mean for the future of disease discovery and attribution?

Giovanni DiMaggio · May 2, 2022 at 10:23 pm

At the end of this article, you state that there are no treatments for NF1. Are there experimental or holistic treatments that have remedied some of the symptoms of NF1 or anything to help patients live with it?

admin · May 12, 2022 at 2:45 pm

Hey, Gio! Thank you so much for this question! There has been somewhat of a breakthrough treatment, although not wholly approved for all people afflicted with NF1. It is a drug named selumetinib, and to understand how it works it is important to remember what causes NF1. NF1 occurs when a protein responsible for regulating cellular pathways, neurofibromin, is no longer functional. Without neurofibromin, a specific pathway is able to continually be activated (since neurofibromin operates as the pathway’s “brake”), leading to the uncontrolled division of cells. The drug, selumetinib, stops this pathway at another point, preventing the uncontrolled division of cells, and reducing the growth of tumors. Currently, it is approved for use in children with severe tumors. Other than that, the most viable option for “treatment” is the removal of tumors that show signs of becoming malignant, restrict someone from performing daily tasks, or that cause severe pain.